| Home > China Feature |

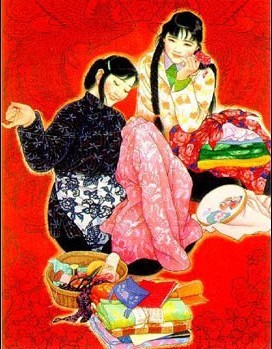

Chinese Needlework

Needlework is included in Chinese folk arts. In the past, it referred to women's needlework-related jobs like spinning, weaving, sewing, embroidering, applique work, patching, pattern cutting, starching, dyeing, and making caps, shoes etc. Any handiwork by women was called "needlework" or "nvhong" in Chinese. The phrase "nvhong" was originally written as "nvgong", which was later used to mean women doing such jobs as spinning, weaving and embroidering etc. To avoid confusion, the original meaning of "nvgong" was shifted to "nvhong".

The Chinese needlework is an art stressing favorable climate, good geographical position, beautiful material and deft hands. As it's been handed down from mother to daughter or from mother-in-law to daughter-in-law for generations, needlework is also called "mother's art".

During the agricultural society spanning 3,000 years or more in China, the farming-oriented thought took root and men plowing the fields and women weaving became an entrenched tradition. Girls at a young age began to learn needle work like drawing patterns, embroidering, spinning, weaving, cutting and sewing clothes etc. It was especially the case in Jiangnan (the lower reach of the south of the Yangtze River). In the Ming and Qing dynasties, along with the booming development of handicraft industry, needlework got widely popular in real sense at that time.

There was no shortage of needlework masters throughout the ages. It is said that Madame Zhao, a concubine of King of Wu during the Three Kingdoms Period, had "three amazing skills": 1) "loom skill"—weaving brocade with dragon and phoenix patterns using multicolor silk threads between her fingers; 2) "needle skill"—embroidering "a map of various states and the five mountains" with a needle and thread on a square silk cloth; 3) "hair skill"—making light silk curtains and screens with hair and silk.

In the first year of Yongzhen Period of the Tang Dynasty, there was an extraordinary woman called Lu Meiniang, who could embroider the seven-volume Lotus Sutra on a one-chi-long silk cloth at the age of 14. Though each character was no bigger than a millet granule, the strokes and dots were quite clear. There were countless needlework masters highly-skilled in all major schools of embroidery styles.

Along with the progression of time, society and technology, manual work has been mechanized, causing a negative impact on needlework. But it still retains its own charm in traditional Chinese culture.

Art

more

moreChina Beijing International Diet ...

Recently, The hit CCTV documentary, A Bite of China, shown at 10:40 ...

Exhibition of Ancient Chinese Jad...

At least 8,000 years ago, Chinese ancestors discovered a beautiful...

Longmen Grottoes

The Longmen Grottoes, located near Luoyang, Henan Province, are a tr...

Custom

more

moreWeb Dictionary

Martial Arts

Tai Chi Master Class Held in Moscow

MOSCOW, June 15, 2016 (Xinhua) -- Students learn from Shaolin ...

Celebriting 70 years' efforts in restoring Mogao...

Work is being carried out at the restoration site of cave No 98 a...

Hong Kong Children's Symphony performs in Seattle

Under the theme of Tribute to the Golden Age, a concert featuring a ...

print

print  email

email  Favorite

Favorite  Transtlate

Transtlate