Hanban shops around for a wider choice

Hanban, the organization that promotes Chinese language and culture, is expanding its work to other fields, although not quite as far as convenience stores.

The leader of the organization hopes its overseas services will become more accessible, with a richer choice for clients, "like 7-Eleven".

"These stores are not very big, but you can see them everywhere and people can get virtually whatever they want whenever they go," said Xu Lin, director-general of Hanban, the nonprofit agency that administers Confucius Institutes worldwide.

"We are trying to do the same. Hopefully, we can also fill our shelves with diversified quality goods. So that those who want to learn Chinese and Chinese culture can have enough choices," Xu told China Daily in an exclusive interview in late August.

There is no way there can be as many Confucius Institutes as outlets of the world's largest convenience store chain. But they have been developing at an impressive speed since the first one opened in South Korea in 2004.

According to the latest figures, 429 Confucius Institutes and another 629 Confucius Classrooms have opened in 115 countries and regions around the world. And about 500 other overseas institutions have applied or shown willingness to collaborate with Hanban.

Meanwhile, the number of foreigners taking the Chinese proficiency test, the HSK, rose from 117,660 in 2005 to 3.5 million in 2012.

With more than 1,000 sites, Confucius Institutes have a widespread presence all over the world that is unmatched by other Chinese agencies or companies. Now in its ninth year, the institute is widely considered the country's best name card with a huge potential for sustainable growth.

"There are more than 10,000 teachers and volunteers in overseas Confucius Institutes and they are the living embodiment of China and Chinese culture," Xu said.

"I know a teacher in Afghanistan who was once only tens of metres away from a bombing on her way to work. They are just investing so much in this course."

Student demand the key

Before joining Hanban as its first director-general, Xu ran the New York Service Center for Chinese Study Fellows for two years and spent another four years in Vancouver as the Chinese counsellor of education.

"For many years, the outside world focused on our efforts to open up our markets and acknowledged our economic growth. But they didn't think much about our education and scientific research, which have also become open and transparent," said Xu, who started working in the Ministry of Education in 1981.

To build stronger mutual trust and seek localization, each Confucius Institute is established and managed by a local college and a Chinese counterpart.

And Hanban's philosophy is not "the faster, the better". Usually, it sends a teacher to the applicant college to see whether there really is a huge demand for learning Chinese and conducts a thorough survey before establishing an institute.

Currently, the United States is leading with 96 Confucius Institutes - four more than the total number of the second to sixth hosts - Britain (24), South Korea (19), Russia (18), France (17) and Germany (14).

"Another 70 colleges (in the US) are still waiting in line," Xu said.

The development, however, has not been without challenges. "At first, we were even suspected of being an intelligence agency," she said.

The tension was highlighted when the US government signed a controversial visa policy in May last year that would force 51 out of 600 Chinese teachers at 81 Confucius Institutes at the time to leave the US in six weeks.

The US Department of State, however, changed the policy after receiving letters from dozens of university presidents who were against the move.

"The driving force is the students and the communities that the colleges serve," Xu said. "They want to learn Chinese and Chinese culture, especially the businesspeople in small and medium-sized enterprises that trade with China.

"The colleges have to respond to the community and the government has to respect the colleges."

Charting a new course

Although China has a long and rich history, to indulge too much in that history doesn't do you any favours when it comes to cross-cultural communications.

"You have to tell the story with a modern flavour, otherwise the audience will lose interest," Xu said.

"Our teachers are good at telling the ancient story but that is not enough. Except for scholars and those who have a special interest in history, people can't swallow too much history and need something more practical and fun."

If You Are The One, one of the most popular Chinese TV dating shows, has been introduced to some Confucius classes for adult students.

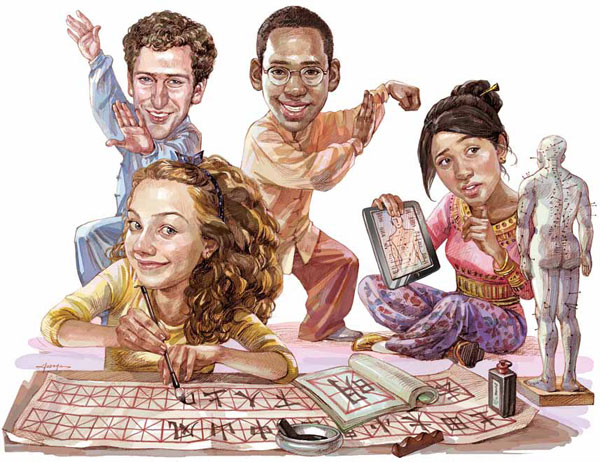

In addition, several specialised institutes have been established and the online study system has been expanding during the past few years.

In 2007, the first two specialised institutes opened in the UK - one for business at the London School of Economics and Political Science and another for traditional Chinese medicine at London South Bank University.

Now, you can also go to Bingham University in New York to learn about Chinese opera or the rapidly developing Chinese tourism sector at Griffith University in Australia, among other choices.

In 2008, Hanban launched Confucius Institute Online to provide a multimedia platform for Mandarin learners. It now has 46 language versions.

However, face-to-face teaching is always the first choice when resources are available. For Hanban, it is increasingly a challenge to send enough bilingual teachers abroad to meet the rising demand. While the Alliance Francaise and the Goethe Institute can hire many local teachers, that is hardly the case for Confucius Institutes because Chinese-speaking teachers are far less common.

"You can find more than 100 colleges in China that have German and French majors, but Chinese is relatively new in other countries despite the rapid development in the past few years. We still have a long way to go," Xu said.

"I have a dream. That one day every speaker at the National Chinese Language Conference can give a speech in Chinese," Xu said in English at the closing ceremony of the 6th National Chinese Language Conference in Boston in July.

"It will probably be realized years after my retirement. But I believe it will come true one day."

Teachers bring home fresh ideas

When you give someone a hug, you usually get one in return. This is exactly what hundreds of Chinese teachers and volunteers have experienced after working for Confucius Institutes overseas.

"Almost every teacher who has taught abroad would say that he or she has lived an extra life compared with people who haven't had that experience," said Xu Lin, director-general of Hanban, the Confucius Institute headquarters in Beijing.

"Their horizons were broadened and their lives changed in many ways, after meeting people and seeing things they had never imagined."

Every year, Xu's organization sends about 10,000 Chinese teachers and volunteers to teach at Confucius Institutes and Confucius Classrooms in more than 100 countries and regions around the world.

Most of them are from Chinese universities, some are college graduates. They stay abroad for a maximum of three years, teaching Chinese language and culture, according to Xu.

"They have to overcome many difficulties in everyday life and adapt to differences in culture and customs, but they also learn a lot," she said.

For one thing, Chinese teachers are often stunned to see how pupils' interests are highlighted in primary schools in the US and other countries.

"In the US and Britain, you must have at least five students in a class, otherwise it will be closed," Xu said. "So Confucius teachers have to make their classes as interesting as possible; and they often succeed."

Xu said that often, after attending classes for a few months, many pupils did not want their teachers to leave; some even cried when their favourite teacher returned to China.

When these teachers do go home, they apply what they have learned overseas. Xu said that if they continued teaching back in China they will try hard to arouse students' interest and interact with them more than teachers normally do in China.

For a year from July 2010, Ren Zexiang was a volunteer teacher at the Marshalltown High School in Iowa, in the US. She said she was impressed by the easy and happy life at the US campus where students' interests and hobbies were well catered for.

"The school has a lot of selective courses for students to choose from, including carpentry, pottery, cooking and even baby nursing," said Ren, who now teaches at the Yunyang Teachers' College in Central China's Hubei province.

"They don't have homework for winter or summer vacations, and they can take part-time jobs to earn some pocket money."

To apply what she had learnt from the US experience at her college, Ren offered to teach two courses training English teachers for primary schools.

"It makes a tremendous difference when you employ different teaching methods," she said.

"We used to resort to translations when we taught English vocabulary. Now I ask the students to come up with ways - as enjoyable as possible, such as drawing, storytelling and even displaying objects. That way, they learn new words while they're doing these things."

Ren said she would like to teach at a Confucius Institute again, because after working in China for two decades, she has things to share with foreign students, and she also wants to learn more about teaching from her foreign colleagues.

Huang Weichao, who worked at the New Lynn Primary School and Kelston Girls' College in Auckland, New Zealand, in 2011, said he found that teachers and students spent a lot of time "chatting" on carpets in class, where the walls were decorated with students' photos and paintings.

Also, the students were allowed to move about the classroom after just raising their hand to ask for permission.

"In China, this perhaps happens only in kindergartens," Huang said in a report posted at the website of China News Service.

Huang also said teachers at New Zealand schools said "good girl, good boy" a lot to students who have made even the slightest progress or done something the right way. In China, such phrases are reserved for rare occasions.

"We must learn from foreigners in this respect, even if our children have learnt something easy, we should still congratulate them," Huang said.

News&Opinion

more

more- OFFICIAL LAUNCH OF BFSU ACADEMY OF REGIONAL AND ...

- G20: Hangzhou wins world's attention

- How To Buy Happiness - The Investment Of Travel

- Goodbye, Rio; hello, China

- 2016 Yunnan-Thailand Education cooperation and e...

- Nice to meet you---你好中文!

- China sending largest-ever team to Rio

- Going to a top university ’no guarantee of getti...

Policy&Laws

How to Get one Job in China---Beijing policy

A foreigner, right, shows his job application form at a human resour...

Guilin to offer 72-hour visa-free stays

GUILIN - The city of Guilin in South China's Guangxi Zhuang autonomo...

further strengthening the visa regulation of int...

After the promulgation of new Immigration Control Act in China, Entr...

print

print  email

email  Favorite

Favorite  Transtlate

Transtlate