More people interested in Chinese Language

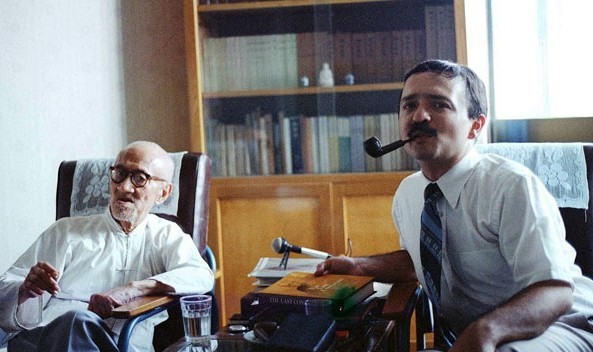

Guy S. Alitto simply dived into the vast pool of classical Chinese when he first tried to learn the language as an adult in the 1960s, but quickly found out that the "sink or swim" approach just doesn't work with the language.

Even after two years of huffing and puffing up the steep slopes of classical texts such as the Analects of Confucius and Mencius, Alitto, then a graduate student majoring in Chinese history at the University of Chicago, couldn't use the language to order food at Chinese restaurants, and couldn't even say ni hao, or hello, accurately.

"We were supposed to learn modern Chinese first and then wen yan wen (classical Chinese), but nobody really knows how it should work," said Alitto in fluent Mandarin. He is now professor of history at the University of Chicago. "At that time, people were not interested in less-developed countries like China. Chinese was an unpopular subject; few people studied it and even fewer knew how to teach it."

Back in the 1960s, hardly any universities in the United States taught courses about China, the exceptions being a couple of elite Ivy League schools. But even in those establishments, knowledge was limited. Some professors could breeze through oracle bones, a form of Chinese script consisting of characters carved into the shoulder bones of oxen or turtle shells, dating from the Shang Dynasty (circa 16th century-11th century BC), but were unable to construct a complete sentence in modern Chinese, he added.

Alitto acquired his Chinese name from his graduate adviser: Ai Kai, which means "optimistic and easily contented". The name was apt: "You had to be very optimistic to be a sinologist at that time," he admitted.

But now, almost every university in the US has courses in Chinese. Alitto's class at the University of Chicago, Introduction to Chinese Civilization, saw undergraduate numbers grow to 127 last year from 70 to 80 just a few years ago.

"More students have become interested in China year-on-year," he said. "If you put the number of students studying Chinese and China's GDP on a graph, they match perfectly.

"Just as the song says, 'The whole world is learning Chinese'," he said, quoting the band S.H.E from Taiwan. "China's booming economy has attracted the world's attention and has also produced a marvelous growth in Chinese studies in the academic field."

In the 1940s, only 26 people studied Chinese language and culture at universities in the United Kingdom. By the 1990s, there were 160 China specialists working in the UK, 60 percent of them conducting research into modern China, according to a report from the National Research Center of Overseas Sinology in Beijing.

The report noted that in 1963 there were 33 people in the US with a doctorate in Chinese studies. However, by 1993, there were more than 10,000 China specialists working for the government or universities, or in business and the media.

In the 19th century there were no academic bodies that specialized in Chinese studies in the US, but by 2012, the number had reached 250. Currently, Harvard University alone boasts more than 10 organizations related to Chinese studies.

"But more important, non-specialists have also developed their knowledge about China and are interested in China. I mean businessmen, school teachers and publishers," said Ross Terrill, a China specialist and research associate at Harvard University's Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies. "Knowledge about China has moved away from pure sinologists. It has jumped out of the box, which is excellent, because understanding China involves various disciplines."

Terrill said there are many students from China on Harvard's campuses, and the Confucius Institutes, government-backed centers that promote the country and its language, have promoted China for a long time. When US nationals travel to South America or Africa, they notice the scale of Chinese projects. "China is part of the world now, not just a place for sinologists to study. You can see for yourself," he said.

Terrill said there are many areas available to people who want to be China specialists. "For instance, we need to read more deeply about China. If you want to write a doctoral thesis on the life of Chiang Kai-shek, we might need it, because the picture hasn't been totally filled in," he said.

He said there are fields that didn't exist 30 years ago, such as Chinese law. "Now China is building a legal system. People are now able to sue each other. But I didn't even feel that when I was a student," he said. However, foreign sinologists should be purely objective, according to Terrill. "They cannot be like priests announcing a truth with authority," he said. "We only have the authority to tell the facts as we find them."

In the 1980s, Terrill published a biography of Mao Zedong, the Chinese translation of which has sold more than 1.8 million copies in China. "I think I am objective in my book on Mao. This is the advantage of being a foreign sinologist," he said. "But the disadvantage was that I didn't feel fully immersed like those people who lived during the Mao era. I just tried to understand what Mao tried to do, to follow his contradictions, achievements and his failures, and also draw a picture of Mao as a man and of his wife. Chinese readers didn't know a lot about Mao's personal life until my book."

News&Opinion

more

more- OFFICIAL LAUNCH OF BFSU ACADEMY OF REGIONAL AND ...

- G20: Hangzhou wins world's attention

- How To Buy Happiness - The Investment Of Travel

- Goodbye, Rio; hello, China

- 2016 Yunnan-Thailand Education cooperation and e...

- Nice to meet you---你好中文!

- China sending largest-ever team to Rio

- Going to a top university ’no guarantee of getti...

Policy&Laws

How to Get one Job in China---Beijing policy

A foreigner, right, shows his job application form at a human resour...

Guilin to offer 72-hour visa-free stays

GUILIN - The city of Guilin in South China's Guangxi Zhuang autonomo...

further strengthening the visa regulation of int...

After the promulgation of new Immigration Control Act in China, Entr...

print

print  email

email  Favorite

Favorite  Transtlate

Transtlate